Originally published April 1, 2013 in Asian Avenue Magazine

Mile High Matcha

Editorial note: Since date of publication, Lindsey Butler has married and is now known as Lindsey Higo. This change is not reflected in the article.

KYOTO, Japan -- It takes Lindsey Butler an hour to make a bowl of tea.

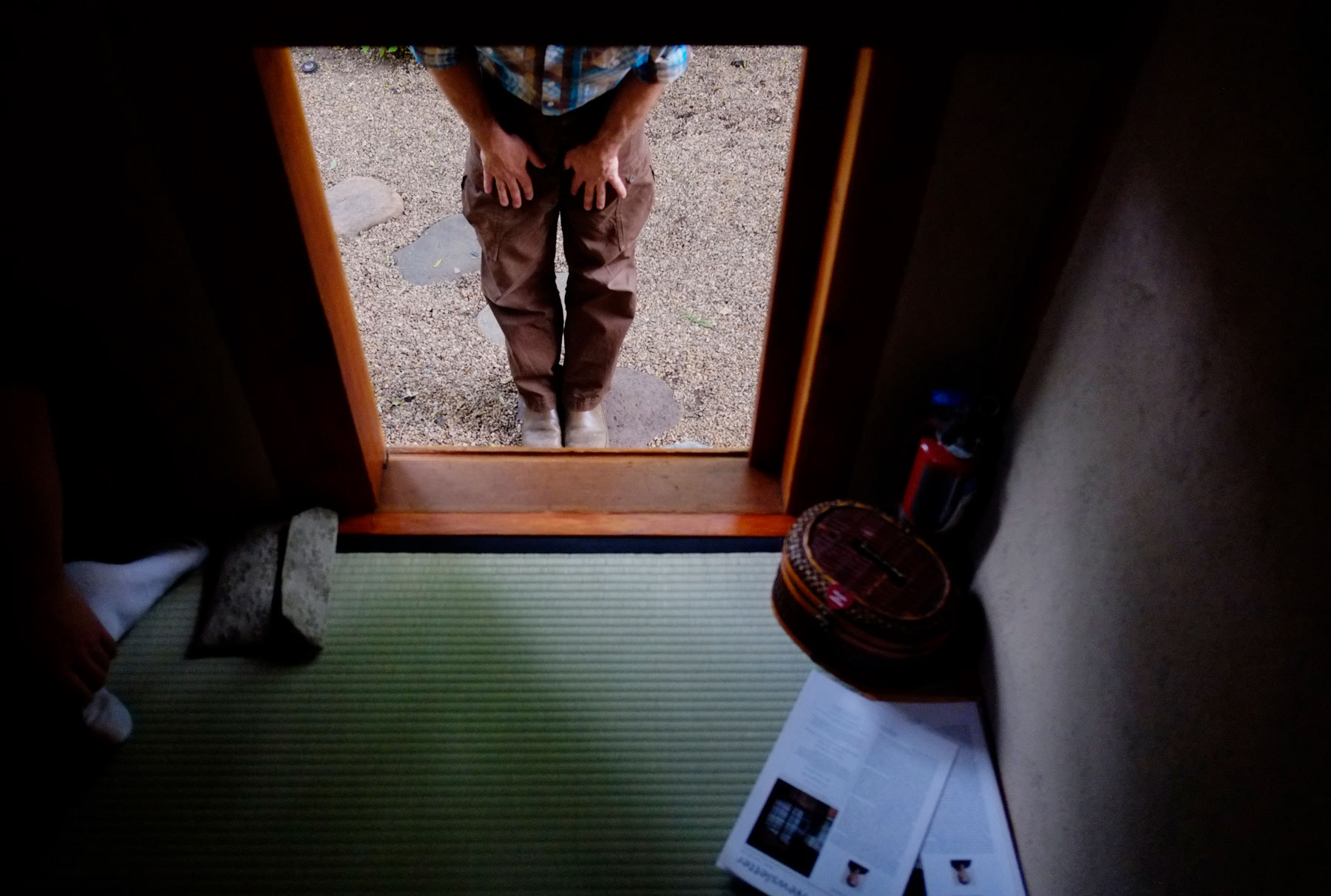

Dressed in a bright blue kimono, the Colorado State University graduate slowly brushes the top of a black lacquer tea caddy with her scarlet silk cloth then, after deliberately refolding the cloth, wipes clean the tiny wooden tea scoop with it as well. Across the room sit six guests, sitting in the classic "seiza" position with feet tucked beneath them, watching every movement Butler makes with rapt attention.

The guests -- four students, a teacher and a reporter -- do not mind that it takes Butler so long to make their bowls of tea. The students are, like Butler, part of the Midorikai program at the Urasenke Center in Kyoto, Japan, a year-long scholarship program that brings foreigners to the heart of the art of Japanese tea for intensive, hands-on training. All six of them, like Butler, are dressed in full formal kimono.

Butler finishes wiping the inside of the first tea bowl and begins to scoop mounds of matcha, a special powdered green tea, into the bowl, followed by a ladle of steaming water. Picking up a spindly bamboo whisk, she leans over the bowl and begins churning the powder mixture into a thin, frothy tea.

The first guest stands, retrieves her bowl of tea and returns to her original position. They bow in unison as she thanks Butler for the tea.

One down, five to go.

On the opposite side of the world, Mike Ricci watches his students as they go through similar motions inside an intimate four-and-a-half tatami mat tea room at Naropa University in Boulder, Colo. Unlike Butler, Ricci and the students in the tiny teahouse are dressed in slacks and t-shirts, practicing the deliberate art of Chado, literally "The Way of Tea," in the comfort of their more casual Western clothing.

A practitioner of tea for 13 years, Ricci is Butler's sensei, or teacher, in Colorado, where she first began practicing in 2007. Eleven years after leaving to attend Midorikai himself, Ricci has sent his own student to study in Kyoto for the first time in his time as a teacher of tea.

Butler's training is the next chapter in a long history of practicing the ancient Japanese art of tea in the state of Colorado, where it is studied and taught by dozens of people ranging from first-time participants to licensed teachers.

In 2001, Ricci attended Midorikai after being recommended by his sensei and former head of the Boulder Zen Center, Hobart Bell. In turn, Bell had been recommended by his teacher, Kim Thrasher.

"There's a kind of lineage, passing this tradition along from teacher to student," Ricci said. "Lindsey represents the next generation of tea in Colorado."

The Midorikai Program, started in 1970 by Sen Genshitsu Hounsai Daisosho, the former head of the Urasenke Headquarters, is a full-ride scholarship worth about $35,000 for students from around the world to live and study in Japan at the official school.

Ricci was served his first bowl of tea at Naropa University in 1999, and he's been returning the favor and teaching there for eight years. In addition to Naropa, Ricci has built a tea room and garden in the basement of his Fort Collins home, where he and a few other "tea people," as they refer to themselves, practice.

Ricci had become deeply interested in Zen Buddhism and discovered tea as a way to simply his life and focus inward to achieve some measure of peace in a fast-paced American society. After studying with Bell for two years, Ricci decided it was time to take it to the next level by applying to the Midorikai program.

"I basically quit my career, sold almost everything I owned and went to Japan to study tea," Ricci said.

In the very same classrooms Butler is studying in today, Ricci dove into the unimaginably complex and intricate world of Chado.

The culture of tea in Japan was a shocking difference from his studies in Colorado, where much of the practice was focused on form and the contemplative nature of tea.

"I hard a hard time studying at Urasenke at first, there were things that I really struggled with," Ricci said. "I didn't really understand it at first, but there's so much focus on learning the history of the utensils and be able to identify the utensils, there was emphasis on being able to recognize patterns of cloth that date back to the Ming Dynasty (in China)."

Chado as it is practiced today was developed into its modern form by Japanese Tea Master Sen No Rikyu in the late-1500s. Rikyu was instrumental in simplifying tea ceremony from the expensive and aristocratic Chinese-influenced affairs into the minimalistic, Zen-like practice it is today.

Unlike many tea instructors, Ricci does not charge his students for his tutelage. Instead, he relies on donations from his students to purchase necessary materials for the practice, such as the matcha powder, the utensils and other supplies.

"Everything that we put into tea in Colorado is our blood, sweat and tears, it all comes from us. Everything we do is put together with our own hands," Butler said.

Although they are as close as any club, the loosely bound group of Urasenke-style tea practitioners is not part of any official organization, although they are still recognized by the Urasenke Headquarters. Ricci feels that money and bureaucracy should not be an obstacle for people who want to study tea.

"If we keep our group open, people can come and do as much tea and learn about as much tea as they want without any requirements or obligations and in that way I believe it's more in the spirit of tea," Ricci said.

"We have a solid group of people who love to do tea and they do tea for no other reason than to do tea. They're not here to hang a certificate on the wall."

In places like California, Washington and Minnesota there is often a high volume of people wanting to study tea, resulting in waiting lists to join the organization and students alternating days with their sensei. In Colorado, however, there has never been a dearth nor an overabundance of people seeking to learn the way of tea.

"Boulder and Fort Collins both seem like great cities to foster (tea culture), but the numbers (of practitioners) have been pretty low over the years," Ricci said. "It's a little surprising to me that we don't have a bigger group, but at the same time it's always been comfortable."

In addition to Ricci's house, a number of other students have built tea rooms into their own homes, where they and other students meet to practice sometimes twice per week.

Learning the Way

In Japan, matcha has enjoyed a long-standing popularity as flavoring for anything from shaved ice to chocolates and hard candies. Only recently has the matcha madness reached American shores, inspiring ice cream flavors, Starbucks' Green Tea Frappuccinos and pastries.

However both in Japan and in the United States, the vivid green tea is hardly ever consumed in its plain form outside of tea gatherings.

"(Chado) went from being a major part of Japanese lifestyle to becoming more of a cultural novelty," Butler said. "People think everyone in Japan does tea, which is a total lie."

There are two basic methods of preparation for matcha within the realm of Chado. The first is "usucha," or thin tea, which is watery with a slightly bitter flavor. The second, "koicha," or thick tea, is used mainly in more formal tea gatherings and is a higher quality tea with a sweeter flavor.

During a full formal tea gathering, known as a "chaji," both thin and thick teas are served, in addition to a meal called kaiseki and occasionally sake as well, and can take up to four hours to perform. The abbreviated tea gathering, known as a "chakai," can be as short as 45 minutes and only thin tea is consumed.

Each type of tea, thin and thick, are accompanied by their own individual types of Japanese sweets, called "wagashi," as a way to offset the bitter flavor of the ground-up green tea.

In either case, the tea itself is a simple combination of powdered tea leaf and hot water.

Chado, also called "Sado" or "Chanoyu," is more commonly known in the Western world as "tea ceremony," but it is a term that is considered inaccurate among many tea practitioners.

"It's not a ceremony, it's an event. It's about bringing people together," Butler said. "You're creating a once-in-a-lifetime experience every time you make tea."

In addition to hospitality purposes, such as to welcome a visiting dignitary, gatherings are often held in recognition of seasonal events, holidays and other special occasions.

Instead of the consumption of tea, Chado focuses largely on appreciating everything surrounding the tea itself, such the garden and weather outside, the flower arrangement, hanging scroll, the sound of pouring water and the whisk creating the tea.

"You enter each moment as if it was a special moment," Ricci said.

A tea gathering represents a number of independent arts in a unified setting. The arts of calligraphy, flower arranging, pottery, woodworking and confectionaries are important elements of the experience.

"Chanoyu is often called 'the quintessence of Japanese culture,'" said Sen Soshitsu Zabosai, the 16th generation Iemoto, or head, of the Urasenke School in a statement in the March 2012 issue of the Urasenke Newsletter. "Alive in it are many forms of culture which have been fostered alongside peoples' lives... hence, to come in touch with Chanoyu helps (one) to become familiar with Japanese culture and life."

The significance of every movement, from ducking to enter the tea room to the way each utensil is held by the host, cannot be understated.

"Tea has a flow and a pattern to it that's supposed to be natural, but I think it's a harder concept for Westerners to grasp," Butler said.

Unlike in martial arts where proficiency in the art is measured through a colored belt system, Chado is ranked based on the licenses earned by the individual host. These licenses grant the practitioner the ability to learn new procedures, which vary based on complexity, formality and other factors.

"The philosophy of the practice is to start at 'one,' go to 'ten' and then come back to 'one.' Through that whole process you gain a deeper understanding of what 'one' is all about, and of what 'ten' is all about, and what it took to get there," Ricci said.

"They kidnap you, they blindfold you and drop you in a forest and you have to find your way," Butler said. "They say that 'Chado' is the 'Way of Tea,' but there is no path. You make your own."

One of the biggest gaps in understanding of Chado among most Westerners is in the snail's pace in which it takes to create a bowl of tea.

"In America, we can go to Starbucks and order our tea and get it in two minutes flat. They don't understand why we have to slow it down," Butler said.

For tea practitioners, however, time seems to lose meaning within the confines of the tea room. One famous scroll even describes the feeling with the phrase, "Nights and days are long inside the jar."

"We could sit and have tea and spend five hours at practice and it would just fly by. It's something you have to experience to know how it feels," Butler said. "It's what makes tea really unique, that you are able to create a place like that where time stands still."

Colorado Chado

Practitioners of Chado have been around in Colorado for generations, possibly dating back as far as World War II, when Japanese-Americans were sent to internment camps across the country, including one in Grenada, Colo. Green tea was grown in the camp's farms and consumed in ceramics designed for drinking tea by the Japanese-Americans being held at Camp Amache. While there is no conclusive evidence that it was formally practiced at this particular internment camp, it was one of the cultural activities practiced at other internment camps around the country.

Current day members of the Japanese tea community in Colorado represent the two main traditional schools of teaching, although there are dozens of smaller lineages in Japan. Butler, Ricci and many of Ricci's students are members of the Urasenke lineage, while the other major school of tea in Colorado is known as Omotesenke.

Unlike Urasenke, which is practiced in Colorado primarily by non-Japanese, a large portion of Omotesenke practitioners are of Japanese descent. A main reason for this demographic discrepancy owes to the fact that Urasenke's mission includes the effort to spread the art of Japanese tea overseas to foreigners. It's that mission that led to the creation of Urasenke's Midorikai program.

Differing stylistically from Urasenke, Omotesenke is the school of teaching that is practiced inside the tea house at the Denver Botanic Gardens' Japanese Garden. Some of the differences between the two styles include types of utensils, the amount that they whisk their tea and in the various small nuances of being a guest or host. Despite their differences, both schools are descended from Rikyu's teachings and are thus practiced in the same spirit.

Designed in 1971 by the late Dr. Koichi Kawana, the tea house at the Denver Botanic Gardens was built in Japan, disassembled and then shipped to Denver, where it was reassembled in its current form. The only Omotesenke-style tea garden in the United States, according to officials at the Denver Botanic Gardens, the tea house is home to Shofu-Kai, a society of approximately 30 tea practitioners led by Tokiyo Imanaka.

The tea house is a standard four-and-a-half mat (approximately 9x9 feet) room, but what makes it unique is the lack of two of the walls, where a small classroom is built around the outside. During the spring and summer, Shofu-Kai hosts classes where the public can sign up and attend a demonstration, eat traditional sweets and try the tea. The goal is to help the public understand the complex and enigmatic art of Japanese tea.

"Many people misunderstand 'tea house' because I think the naming is bad," said Ebi Kondo, curator of the Japanese gardens at the Botanic Gardens. "'Tea house' sounds like a cafe, so many people expect to come here and be served tea by a lady in a kimono. Our interpretation goal is to help people understand the concept of tea ceremony. Drinking tea is a very small part of tea ceremony. It's about wellness of the mind and soul. It's about appreciation of the season and nature."

Imanaka came to Colorado by way of Los Angeles 20 years ago and took over the adult education duties at the Botanic Gardens from her predecessor, the late-Kathryn Kawakami, in 1995.

After a brief introduction on the background of Chado and a simple demonstration, Imanaka, who began practicing tea at the age of 10 in post-war Hiroshima, calls up volunteers to try their hand at a tea gathering. Starting with sekiiri, or entering the tatami mat room, she walks the volunteers through the entire process, from bowing in front of the scroll to the procedure of drinking the tea.

"It's a very basic introduction to tea ceremony, the tea house and garden. Most people are just curious and this is just the first step, they're not looking for an in-depth explanation," Kondo said.

At first there was some hesitation by officials at the Botanic Gardens toward making the Chado classes available to public visitors of the garden.

"Tea ceremony is very complex and traditional tea ceremony doesn't have the concept of 'open to the public;' it's a very private event," Kondo said. " (But) if we prefer to walk away, these people will never experience something like this. This is a very simple yet complex and meaningful cultural event and our mission is to translate that to the American public."

In Japan, practitioners of the two main lineages of Chado do not often mingle with each other, much less practice together. Colorado differs in that respect, as the community of tea practitioners is so small it breeds a kind of intimacy and familiarity between them.

"It's a lot more about feeling and community around tea ceremony (in Colorado)," Ricci said.

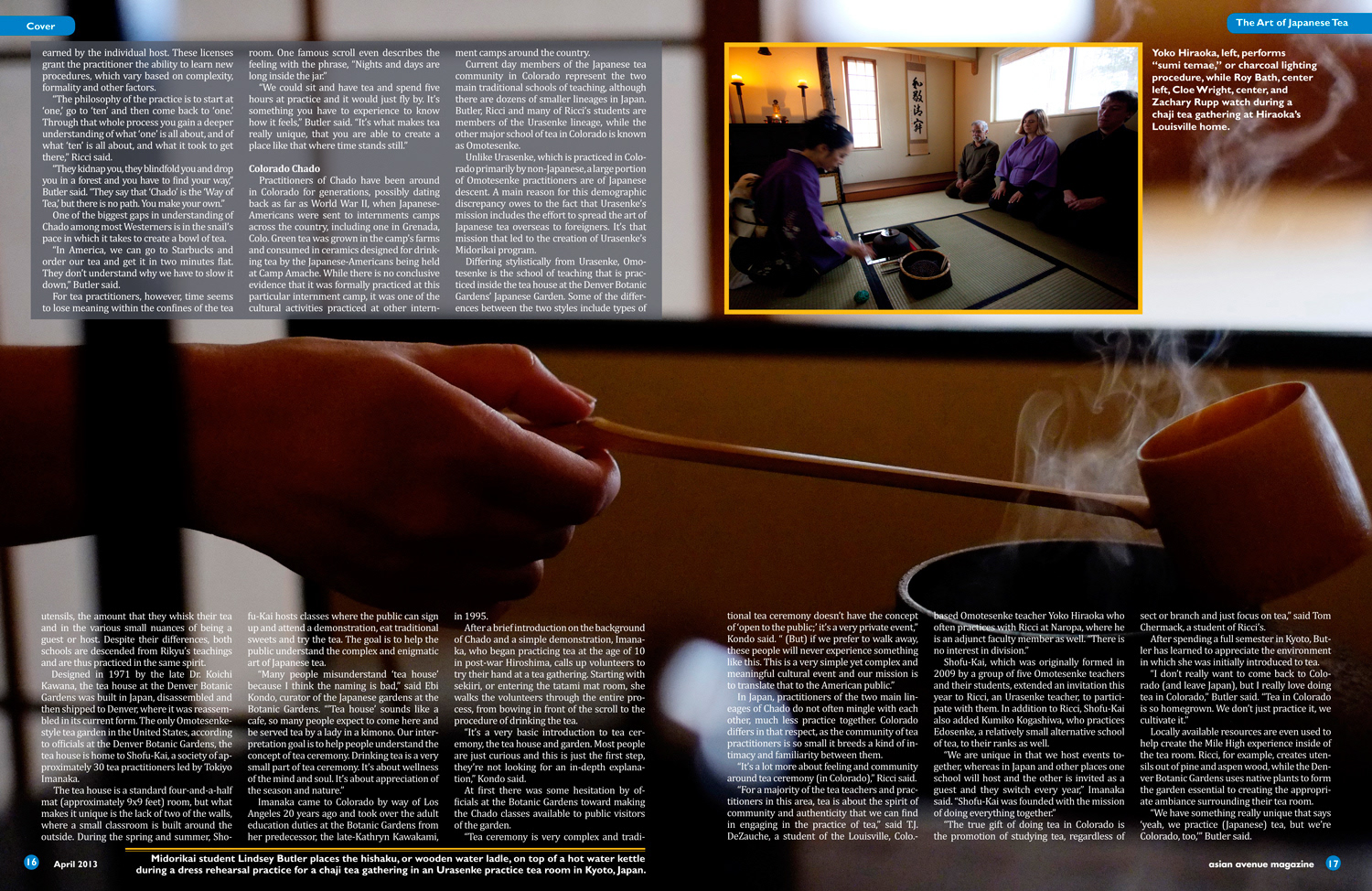

"For a majority of the tea teachers and practitioners in this area, tea is about the spirit of community and authenticity that we can find in engaging in the practice of tea," said T.J. DeZauche, a student of the Louisville, Colo.-based Omotesenke teacher Yoko Hiraoka who often practices with Ricci at Naropa, where he is an adjunct faculty member as well. "There is no interest in division."

Shofu-Kai, which was originally formed in 2009 by a group of five Omotesenke teachers and their students, extended an invitation this year to Ricci, an Urasenke teacher, to participate with them. In addition to Ricci, Shofu-Kai also added Kumiko Kogashiwa, who practices Edosenke, a relatively small alternative school of tea, to their ranks as well.

"We are unique in that we host events together, whereas in Japan and other places one school will host and the other is invited as a guest and they switch every year," Imanaka said. "Shofu-Kai was founded with the mission of doing everything together."

"The true gift of doing tea in Colorado is the promotion of studying tea, regardless of sect or branch and just focus on tea," said Tom Chermack, a student of Ricci's.

After spending a full semester in Kyoto, Butler has learned to appreciate the environment in which she was initially introduced to tea.

"I don't really want to come back to Colorado (and leave Japan), but I really love doing tea in Colorado," Butler said. "Tea in Colorado is so homegrown. We don't just practice it, we cultivate it."

Locally available resources are even used to help create the Mile High experience inside of the tea room. Ricci, for example, creates utensils out of pine and aspen wood, while the Denver Botanic Gardens uses native plants to form the garden essential to creating the appropriate ambiance surrounding their tea room.

"We have something really unique that says 'yeah, we practice (Japanese) tea, but we're Colorado, too,'" Butler said.